How India’s ‘COVID Warriors’ Used Social Media To Serve Their Communities

In mid-2021, India was crumbling under the pressure of an intense COVID-19 wave, caused by the Delta variant of the SARS-CoV-2. But at the same time, misinformation was spreading exponentially – adding to the fear and anxiety of the time.

Thousands of people were scrambling to find oxygen cylinders and hospital beds for their loved ones infected with COVID-19, while others were struggling to recover completely from a previous COVID-19 infection and did not know what was happening to their bodies. Mis- and dis-information about the virus were rampant, creating widespread chaos in the country.

Watching this situation unfold in front of his eyes pushed Sai Charan Chikkulla to take matters into his own hands.

“A man lost his mother to COVID-19 after being shunted from one hospital to another due to lack of a bed with oxygen supply. He saw his mother die in an ambulance waiting for an oxygen-bed in a big government hospital because he didn’t know where else to take his mother,” Sai Charan told Health Policy Watch.

A regular user of Twitter, the 29-year-old Hyderabad-based entrepreneur immediately decided to pick up the phone and start dialling. His idea was simple: to call hospitals in the region, enquire about the bed availability and the criteria for admitting patients and post the information on Twitter with the relevant hashtags.

Sai was not the only one leveraging the platform to do good during the pandemic in India. Several others across the country used their social media profiles for good during a wave that killed at least 240,000 persons in India.

Twitter as a dashboard for hospital beds

“I used to collect data [of bed availability] from one hospital. I immediately posted on Twitter. Around 200 people reached out to me after that asking for more information on the availability of hospital beds. That’s when I realised the situation on the ground was horrible,” he recollected.

Charan expanded his calls to cover more hospitals and eventually began focussing on government hospitals from across his state, Telangana, and posted the details on Twitter regularly.

“The charges in government hospitals were lower and affordable to people. So I started collecting up to date information from these hospitals, the phone number of the person in charge there and posted on Twitter with their consent.”

Sai Charan getting an award from a state minister for his work during COVID-19.

His volunteering efforts also expanded to posting real-time, reliable and verified information about the availability and prices of treatments remdesivir and tocilizumab, which were in demand in India during the worst peak of COVID-19.

Sai’s efforts led to at least 1,500 persons securing hospital beds during the time of need in Telangana. Acknowledging his work during this period, the Government of Telangana honoured him with a “COVID warrior” award in November 2021.

For DVL Padma Priya, life has not been the same since April 2020 when she got her first COVID-19 infection. While getting tested for COVID-19 was challenging as she was not in one of the “high risk groups”, the period after recovery wasn’t a breeze either.

“My sense of taste and smell did not return till July and in July, 2020, I fainted. I had gone grocery shopping and I completely blacked out,” she shared with Health Policy Watch.

“My doctor put me on supplements and told me to drink more water, but I was having severe issues like with my heart rate since then and I had severe tachycardia and I would faint every time I would change positions.”

Long COVID unknown

At the time, long COVID was not as known and patients often faced gaslighting from the doctors or inconclusive diagnosis.

“Long story short, it took a lot of self-advocacy for myself because I was basically being told I am anxious. I had to advocate a lot for myself to finally find a good doctor in Hyderabad who ran a couple of tests and said, ‘It looks like you have some sort of autonomic dysfunction’,” she recollected.

A media entrepreneur, Priya shared these experiences on Twitter and received solidarity from across the population who were also experiencing similar symptoms.

This prompted her to start a group on the instant messaging platform Telegram, which became a forum for people to discuss their symptoms, doctor visit experiences and updated studies on long COVID.

“We’ve had a lot of webinars with groups of experts like mental health experts, neurologists etc since they understand what the symptoms could be and what people need to be aware about long COVID.”

At its peak, the group had around 500 members, who used the platform to share tips on how to advocate for oneself to the doctors and what to look out for after testing negative for COVID-19.

Padma also started a “Long COVID survivors India” handle on Twitter and Discord, mainly to disseminate information and create awareness among the people about the various effects of COVID-19 on the human body.

Verified information as the right weapon

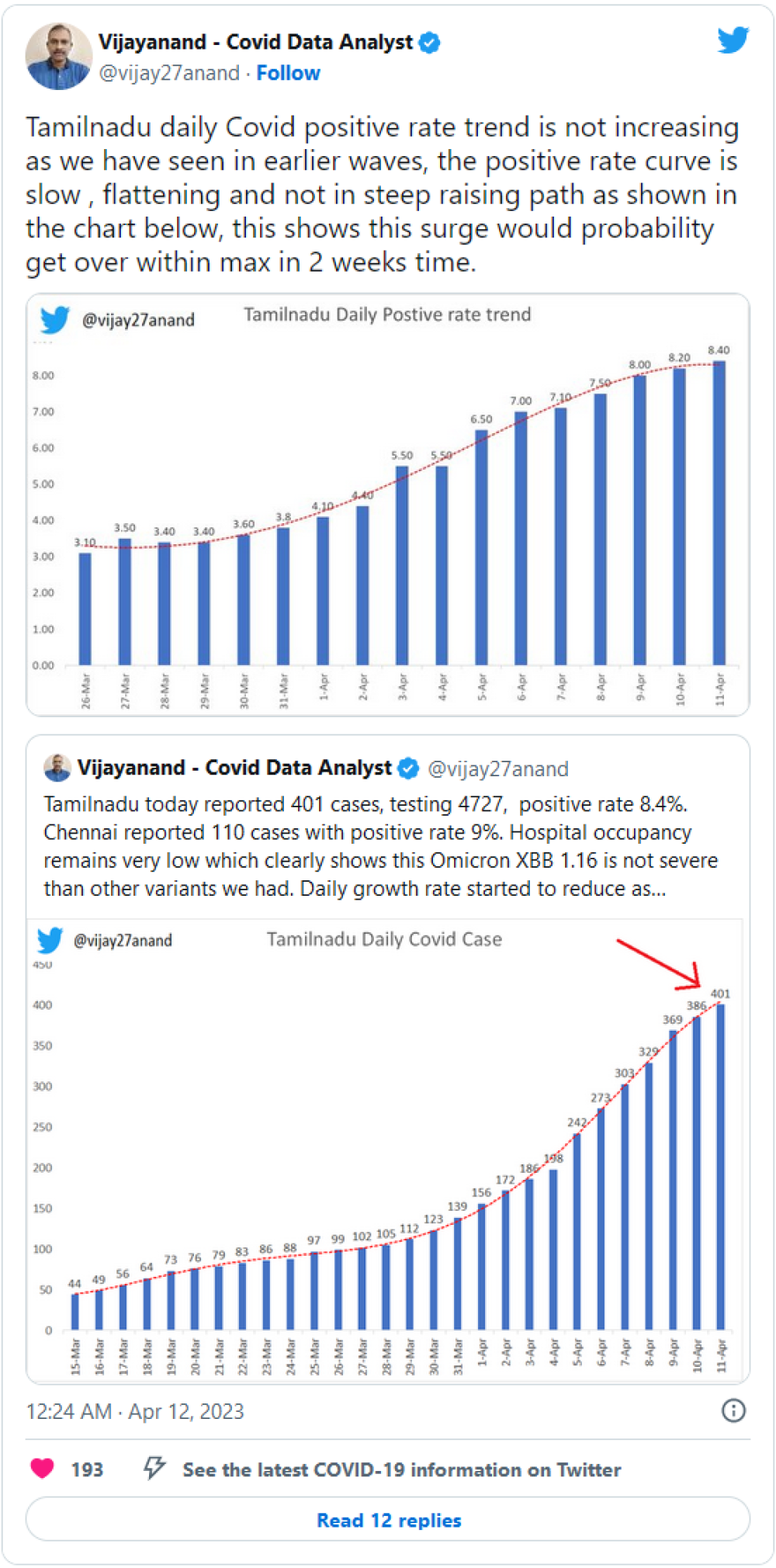

In April 2020, Vijay Anand, a Chennai-based techie was witnessing a barrage of fake news about COVID-19 being spread on WhatsApp and Twitter. The information being spread ranged from rumours around the spread of the virus in his city to “instant magic cures” against SARS-CoV-2. The urge to address these messages drove Vijay to use his Twitter account to do something meaningful.

“I started looking into government data [on COVID-19 cases]. I could find a lot of people analysing similar data in the US and UK but couldn’t find anyone doing it in India at that time. I saw an information vacuum there and wanted to fill it,” he explained.

In an interview to Health Policy Watch, he added that the idea was to study the pattern and interpret it into useful and actionable information. “I wanted to tell people what is really happening and if there is a need to panic or worry about the [COVID] wave.”

Vijay tweeted at least once a day with the data released by the government authorities and his analysis based on the numbers. His tweets often included details of the positivity rate and reproductive rate of the virus and the outlook for the next few days.

“I used to follow a lot of epidemiologists from established organisations like the Indian Council for Medical Research (ICMR), the US CDC and the UK, to understand what they’re trying to do in the rest of the world,” he elaborated. “And I used to spend about two to three hours a day just reading white papers that were published on COVID-19 to arm myself with the knowledge.”

Accepting that he is not a medical doctor and his messaging was inaccurate at times, Vijay was always open to correcting his tweets based on the feedback from experts.

“So, because a lot of doctors and even senior experts follow me [on Twitter], they just give me some feedback and I just correct [the information I put out].”

His consistent analysis that focussed on cutting out misinformation and fake news earned him praise from several government officers.

Image Credits: Unsplash, Supplied.

This article was written by and first appeared in HealthPolicy Watch here.