One Pandemic: Two Heroes – How Social Media Drove Debate Around Mexico’s Response to COVID-19

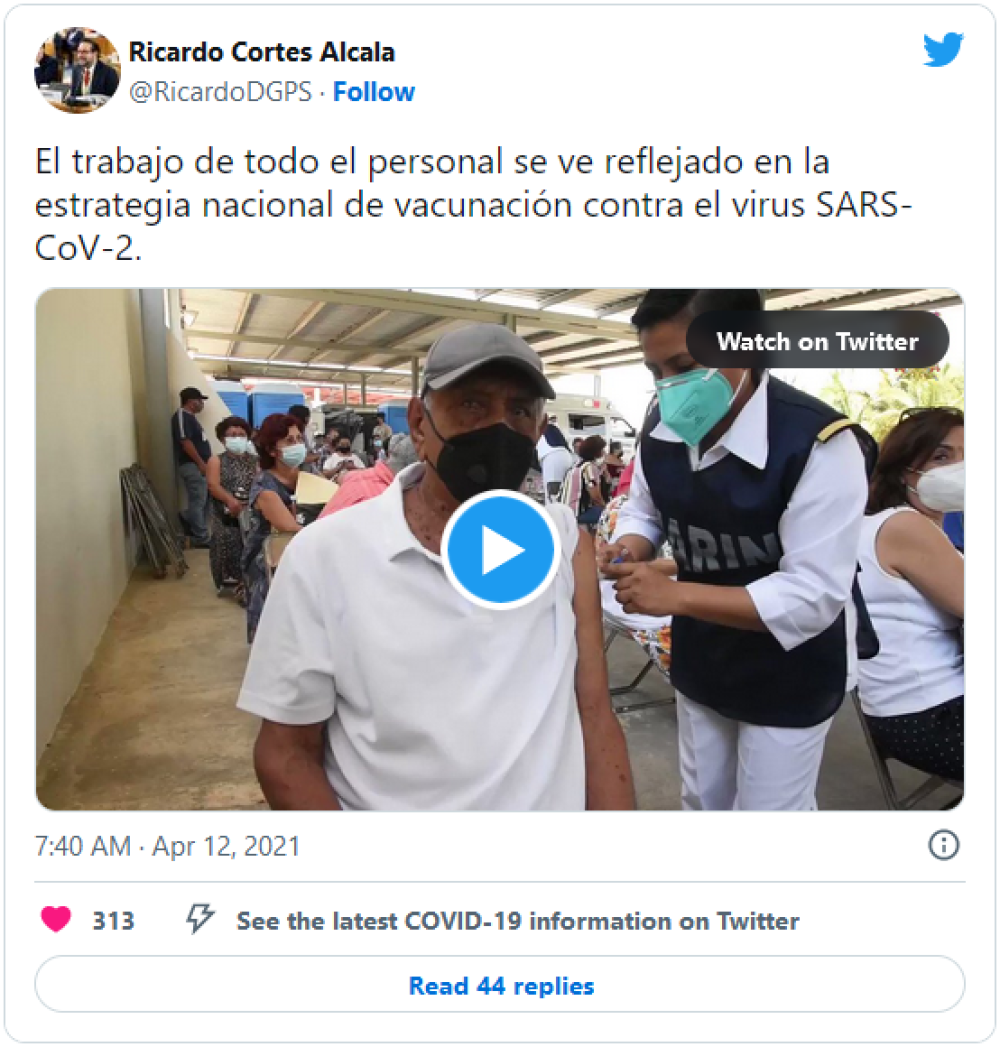

COVID vaccination in Mexico in April 2021, as captured by a Ministry of Health promotional video. The debate between critics saying the official COVID response was too weak, and government defenders, has been a key social media theme.

February 20, 2020, was the day on which the first COVID-19 case was recorded in Mexico. The infected person was a 35-year-old man from Mexico City, the capital of the Latin American country, who had travelled to Italy.

The announcement was made by Hugo López Gatell, epidemiologist and undersecretary of Prevention and Health Promotion of the government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO). The news, however, did not take Mexicans by surprise. Since the end of January, a possible case had been detected but never confirmed, followed by a suspicion of the virus in another 30 people. As a result, the government imposed a strict protocol for identifying infections in air terminals and mandatory sampling in suspected cases. It also asked all citizens with symptoms such as fever, cough and runny nose to go immediately to the doctor, keep common areas clean, avoid using public transportation and avoid leaving their homes.

The AMLO government’s decision to introduce these measures so early undoubtedly allowed Mexico to be one of the Latin American countries that responded most quickly to the first signs of the pandemic in other continents, such as Asia and Europe. However, it began the fight against COVID-19 with a precarious hospital infrastructure, which hindered care of the sick.

Upon taking office as president, AMLO described the state of the country’s health as “a disaster.” There were abandoned hospitals and continuous deaths of people due to problems in health services, which undoubtedly made the pandemic much more difficult for Mexicans. This situation was due to several factors: the corruption of state and governmental entities in Mexico, which meant that the money that should have been allocated to hospital infrastructure never arrived; the lack of health personnel; and a historical under-investment in spending for this sector.

Héctor Valle, executive president of the Mexican Health Foundation, stated that “access to medical services was almost non-existent due to the lack of doctors, medicines and hospitals. For 30 years, Mexico has been a country that invests less than six percent of its gross domestic product in health, while the minimum that other member countries of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development invest is nine percent.”

In this context, management of the pandemic on all communication channels was vital, especially on social networks, which are a space for venting, searching for information and creating communities.

Social networks, the spearhead amidst the crisis

‘COVID does not discriminate – why should you?’ IOM media campaign addressing stigmatisation of migrants, launched in April 2020

Due to pandemic confinement, social network users in Mexico increased by 12.4% compared to 2019. In addition, Mexicans reported spending an average of nine hours surfing the net, with the most visited sites being Google and Facebook.

This reality made the networks a critical space Mexicans during the pandemic. Social media became the setting for in-depth discussions about the government’s handling of the pandemic and for launching campaigns that sought to combat misinformation and discrimination during the emergency.

One example was the campaign created by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), “COVID-19 does not discriminate, why should you?,” which aimed to inform and sensitise Mexican citizens and public officials about the reality. The premise was that any migrant was equally (or more) vulnerable to COVID-19, and that it was urgent for the government to move public policies to eliminate stigmas and discrimination against migrants – whose mobility and marginalizations made them especially vulnerable to both catching the disease and transmitting it.

Another example was the alliance between the United Nations (UN) and various Mexican media to combat disinformation about the pandemic, mainly through social networks. According to Jenaro Villamil, president of the Public Broadcasting System of the Mexican State, an estimated 62% of pandemic news spread mainly through social networks sought to discredit scientific attempts to find a vaccine. Likewise, the Mexican government used press conferences on social networks, 451 in total, to keep the population informed about the progress of the pandemic.

Social media also became a channel for complaints about government pandemic responses

Laurie Ann Ximenez Fyvie, a leading microbiologist, promoting her book criticising the government’s management of the pandemic on Twitter.

Despite these efforts, social networks also became the channel not only of entertainment for Mexicans during the pandemic but also of complaints towards their government.

By 2023 it is clear that, despite trying to reinvent the health system, the Mexican government’s handling of the pandemic was insufficient: it is the country with the fifth-highest number of deaths in the world due to the virus.

José Parra, a Mexican businessman and senior citizen, recounted his experience with COVID-19: “I have no medical service; it is an incalculable cost. I remember spending three months on oxygen and medication, all expensive. I had no way to go to the hospital. Parra is one of the 33 million Mexicans who, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI), are not affiliated with public or private health services.

Since 2020, social networks have been filled with testimonials from other Mexicans with similar experiences to Parra’s or simply complaining about the government’s poor health management during the pandemic. The following are three examples:

Tweet translation: “How many Mexicans died of Covid-19 in 2020 for lack of vaccines, respirators, medicines, and inputs in the health sector, which was destroyed in 2018? Meanwhile, a baseball stadium for Manuel was funded with economic resources from our taxes.”

Tweet translation: “Mexico ended 2020 with 2,470 deaths of health personnel due to COVID-19, far surpassing other countries such as Brazil (775), United Kingdom (620), India (573), Peru (385) or Italy (279).”

“In 2020, the federal government (of Mexico) spent only 0.9% more than in 2019 in the health sector, DESPITE THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC. It is therefore not surprising the number of deaths (4th place worldwide) we have, much less that we are the worst in terms of medical deaths.”

Although the Mexican government attempted to mitigate the discontent, it could have made more significant efforts to manage the frustration through social networks and to offer solutions during the pandemic.

Two nominees, two opposing visions – one pandemic

Laurie Ann Ximenez-Fyvie, head of the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, NAUM, Mexico

Ricardo Cortes-Alcalá, President, Health Promotions for the Government of Mexico

Two Mexian influencers who have stood out on social media networks – as a result of their positions during the pandemic and post-pandemic are Laurie Ann Ximénez-Fyvie and Ricardo Cortes-Alcalá. Their voices also reflect dramatically opposing views on the response to the crisis – with Fyvie, a leading microbiologist, having consistently taken stances that are deeply critical of government while Alcalá,president of Health Promotions, has been a constant defender.

Both are nominated for the COVID-19 Influencers 2023 Social Media Awards. Sponsored by UniteHealth, with a range of multilateral agency, non-profit and media partners, the awards seek to recognise those who dedicated their time and expertise to influence social media platforms during the crisis positively. However, each nominee represents a polar opposite in Mexican politics and society. Their diverse opinions generate passionate discussions on social networks that show the extreme division caused by the pandemic in Mexico.

Ximénez-Fyvie is head of the Laboratory of Molecular Genetics at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. She has been critical since the beginning of the pandemic of the government’s actions, specifically those of the Undersecretary of Health, Hugo López-Gatell. The scientist has said in media, such as the BBC and on social networks, such as Twitter, that during the two most critical years of the pandemic, 2020 and 2021, Lopez-Gatell’s decisions were driven by political rather than scientific criteria.

She called him the “czar of the coronavirus” and blames him for not having had a structured strategy to stop infections in the pandemic’s early days, counting too heavily on protection from ‘herd immunity’. In particular, she criticized the fact that the Mexican government did not impose any movement restrictions on its borders, which continued to see refugees and migrants moving north, to the United States throughout the crisis.

Her criticism was such that in 2021 she published the book Un Daño Irreparable (An Irreparable Damage), in which she described the allegedly ‘criminal’ management of the pandemic in Mexico. She claimed the government simply did not want to take more forceful measures, as well as strengthening health systems.

Through social networks, Ximénez-Fyvui has continued until today to denounce the lack of transparency and information on the pandemic by the government, the shortage of vaccines in Mexico and the country’s human losses due to the virus. Although her criticisms are severe, the data and the reality of Mexico during and after the pandemic show that they are not unfounded.

Cortés Alcalá, on the other hand, is a field epidemiologist and current president of Health Promotion for the Government of Mexico. He has relied heavily upon social media networks to demonstrate the Mexican government’s progress confronting COVID and in rebuilding the health system. As his tweets and profile illustrate, he presents himself as an official voice for communicating about COVID policies, including heavy promotion of vaccination since the mass rollout of COVID vaccines in April 2021.

Both people also have published attacks against the other. Rather

than delving into such attacks, it is worth mentioning that they reflect

how the pandemic deepened divisions in many countries and increased

polarisation; a situation that does not help any public health system,

let alone that of a country that already had serious problems within its

health infrastructure.

The reality is that both leaders and media influencers had, and still maintain, a pivotal influential role in rebuilding the trust of Mexicans vis a vis health institutions in the post-COVID era. They are proof that social networks are a powerful medium, sometimes even more so than traditional media, by continuing to provide information, mental health support, and a sense of community during and after times of crisis.

Image Credits: @RicardoDGPS, International Organization of Migration , Twitter/@lximenezfyvie, UniteHealth, Twitter/@RicardoDGPS, Unsplash.

This article was written by and first appeared in Health Policy Watch here.